Clinician Well-being Summit

The Summit on Promoting Well-being and Resilience in Healthcare Professionals

by Susan Neale

Summit co-chair Bernadette Melnyk, PhD, APRN-CNP, FAANP, FNAP, FAAN, explained the problem succinctly in her opening remarks: “Even before the pandemic, we had an epidemic of clinician burnout, depression and suicide. Those rates have increased even more because of the pandemic. It is time for urgent action. Our healthcare systems must fix system issues that contribute to this problem. And we have to get faster at translating evidence-based interventions into our clinical settings, not only to improve our population health outcomes, but also to ensure healthcare safety and quality.”

Concern for the epidemic of clinician burnout, suicide and depression sweeping the country led to the inaugural Summit on Promoting Well-being and Resilience in Healthcare Providers in 2018. Since then, awareness has grown about clinician burnout and some progress has been made among policymakers and institutions, but several factors have raised the stress levels of healthcare professionals to a new high, including the global coronavirus pandemic, national political unrest and growing awareness of healthcare disparities across racial and socioeconomic lines.

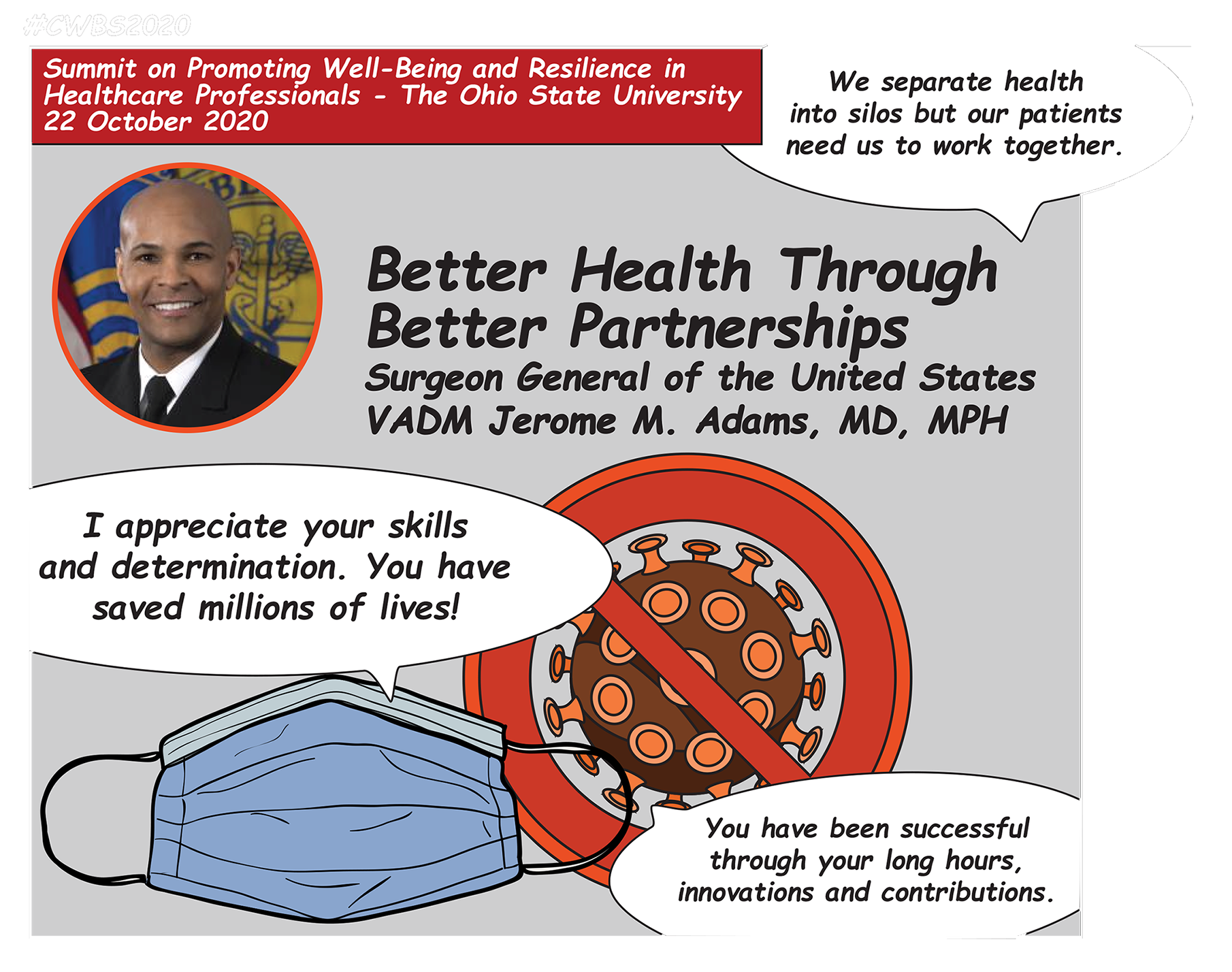

A message from the United States Surgeon General: hope and encouragement

At the time of the summit, over 200,000 COVID-19 deaths had been reported nationwide and a vaccine had not yet been approved. “SARS CoV-2 has shaken the world to its core,” said 20th United States Surgeon General Vice Admiral Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH. “We’ve struggled to protect human life against a novel and deadly adversary.” He praised the medical community for their skills, stamina and innovation in fighting coronavirus, adding, “There’s never been an instance in our lives that more exemplifies the phrase, ‘Trying to fly the plane while we’re building it.’”

Concerned for healthcare providers suffering burnout from dealing with the pandemic, Adams offered praise and encouragement. “I want you to hear from the nation’s doctor that your skills, your stamina, your dedication have truly saved lives — potentially millions of lives. You have been successful.”

Adams urged attendees to watch his TEDtalk on healthcare disparities. “This virus has shown us ... that before you get to those pre-existing medical conditions, there are really pre-existing social conditions that conspire to reduce our resilience, our opportunity and our health.”

“Social factors make individuals more susceptible to infection with COVID-19 … for example, we know that social distancing and teleworking are critical to preventing the spread of coronavirus, yet only one in five African Americans and one in six Hispanic Americans has a job that allows them to telework from home.”

Adams also urged clinicians to promote the benefits of vaccinations, which he called a “cheap, safe, easy” way to improve public health and save lives — not just for COVID-19, but for many infectious diseases such as measles, chickenpox and flu. Presenting progress on a COVID-19 vaccine, he added, “As important as a vaccine is, it means nothing if we don’t ensure uptake and equal distribution.” On behalf of all of the organizers of the summit, Melnyk presented Adams with the National Wellness Leader Award.

The state of clinician well-being today

The current statistics on clinician burnout are devastating. “The CDC has reported that the prevalence of anxiety, depressive disorders and suicidal ideation are up two to four-fold from what it was this time last year,” said Lotte Dyrbye, MD, MHPE, professor of medicine and medical education at Mayo Clinic and co-director of Mayo Clinic’s program on clinician well-being. “In national studies that include healthcare professionals, not only physicians but also advanced practice providers, nurses, pharmacists, residents and medical students, we are seeing prevalence of burnout in around 37-44% and depressive symptoms among 28 – 32%.”

Dyrbye cited factors contributing to clinician burnout, including frustration with the electronic health record, work/home life conflicts, and lack of “work-interest alignment.” “If you can spend at least one day a week doing the most meaningful part of your job, the part you enjoy most, you have substantially lower odds of burnout,” she said. Mistreatment at work, including gender and racial discrimination, is also a factor in burnout, signaling a need for cultural change. Dyrbye recommended the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-being and Resilience’s consensus study report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: a Systems Approach to Professional Well-being,” which is available for download.

Victor Dzau, MD, president of the National Academy of Medicine, presented an update on the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-being and Resilience since the last summit. The collaborative’s actions include a publication urging the United States Congress to create an act to support first responders of the pandemic in their physical and mental well-being, similar to the existing act for 9-11 first responders. In response, Congress is working on passing bill S. 4349, for the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act.

Cynda Rushton, PhD, RN, RAAN, professor of clinical ethics at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, defined another dimension of well-being for healthcare professionals: moral resilience. “Moral adversity occurs when internal or external circumstances or actions produce morally objectionable, troublesome, or unfortunate results that can imperil integrity and well-being,” Rushton said. She invited the audience to share in the chat examples of moral suffering they had experienced, such as the emotional burden placed on nurses working with COVID-19 patients in end-of-life scenarios where no family members were allowed to be present. In the face of moral adversity, Rushton asserted, both individual healthcare providers and the systems they work with must be pro-active in bolstering their moral resilience.

Flourishing, and so much more

This summit did not merely outline the problem, but also offered a wealth of actionable steps to boost clinician resilience and well-being, including sessions on stress-reduction and relaxation, presentations from healthcare systems and professionals on programs that are working for them with measurable results, physical exercise demonstrations, inspiring and useful advice from experts studying resilience and happiness, and even a few laughs from “the healthy humorist” comedian and doctor Brad Nieder, MD, CSP.

Keynote speaker Douglas Smith, MBA, a former business leader whose roles included CEO of Kraft Foods Canada, turned his attention to positive psychology after a life-threatening cancer diagnosis. His job now, as he put it, is helping others find their happiness and learn how to flourish, through his books, seminars and work with his company, Positive Foundry. In his keynote speech, “The Science and Skill of Flourishing,” Smith presented evidence-based tactics for improving resilience based on positive psychology, a branch of psychology started by Martin Seligman in 1988 that focuses on helping people lead meaningful, happy lives.

Smith posed the question, “How do you develop underlying contentment and well-being?” The answer, he said, has to do with how you look at the past—learning from it and letting it go; and how you look at the future—not trying to control it, but accepting whatever diversions come your way. “If you do that, you can live in the present, where so much joy is found.” Smith enumerated many skills for flourishing that can be actively cultivated, including gratitude, forgiveness, being kind, finding purpose, cherishing relationships and facing the future with faith, optimism, flexibility and openness.

Thanking Smith, Dean Melnyk remarked, “There’s a misperception that you’re either born with resilience or you’re not, which couldn’t be farther from the truth. You can and should build it throughout your entire life to prevent chronic physical and mental health conditions.”

Chief wellness officers Melnyk, Johnathan Ripp, MD, MPH, from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Bryant Adibe, MD, from the Rush University System for Health offered evidence-based strategies for building a culture of wellness in organizations and improving population health outcomes. The role of Chief Wellness Officer in academia is a relatively new one, and is already showing great results for the well-being of students, faculty and staff. The three CWOs stressed team-building, ingraining wellness into organizational culture and making wellness initiatives exciting and engaging.

Endnote speaker Betsy Charles, DVM, executive director of the Veterinary Leadership Institute spoke from her backyard in sunny southern California about creating an internal revolution. “We tend to put all our energy toward what we can do systemically to solve the problems we face. We develop programs and policies … in order to try to fix what is very obviously broken. These externally focused efforts are important, but they will always fall short if we don’t spend significant time on ourselves by prioritizing understanding ourselves,” Charles said. She urged healthcare professionals to take time to get to know themselves better and examine whether they have been sabotaging their own resilience with a perfectionist mindset or fears of social comparison and failure.

Interestingly, Charles sees opportunity for emotional growth within the pandemic. “It is time for us to remember that we are exactly who the world needs,” she said. “Yes, we are veterinary doctors, scientists … but we are so much more than that, and it is the 'so much more,' in combination with our training, that the world needs right now.”

The spirit of the summit might best be captured in these closing remarks from Surgeon General Adams: “We are in the midst of a tragic time for many families, but I also think that there is a tremendous amount of opportunity for us to really reshape some fundamentally flawed systems that we work within and that cause our burnout. And my hope is that we will look back at this time with appropriate sorrow for the lives lost, but that we will also look at it as a time when we had our ‘aha moment,’ that moment when we changed these systems for the better.”