Witness to History

by Nicole Rasul

Lieutenant Colonel Karen Vinson-Van Houter (’67) (or Karen, as she asked to be called in this story) has always had a strong sense of adventure. During the early 1960s and the start of the Vietnam War Era, the Rossford, Ohio, native left her small town in the dark of night to join the U.S. military. She was 18 at a time when women had to be 21 to enlist without parental consent.

Lieutenant Colonel Karen Vinson-Van Houter (’67) (or Karen, as she asked to be called in this story) has always had a strong sense of adventure. During the early 1960s and the start of the Vietnam War Era, the Rossford, Ohio, native left her small town in the dark of night to join the U.S. military. She was 18 at a time when women had to be 21 to enlist without parental consent.

“It was June 1963,” the 74-year-old recently said. “I had just graduated from high school and I boarded a bus on the corner at 4 a.m., headed to Fort McClellan in Alabama for Women’s Army Corps training. I left a note on my bed for my family.” Karen’s father soon tracked her down and, after a stern conversation, agreed to sign the paperwork that would enable her to pursue military training.

In the Women’s Army Corps, Karen followed a budding interest in nursing, a field she had discovered in her youth as a Red Cross volunteer at a hospital in Toledo. After a year in the military and having earned the title of certified nursing assistant, she phoned The Ohio State University to see if her earlier acceptance there was still valid. Fortunately, it was, and in the autumn of 1964, while still on active duty, she began her studies at Ohio State, graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing several years later.

From there, a busy and celebrated climb through the ranks of the U.S. military ensued. In late 1967, she was sent to the Vietnam War as a nurse in the Army Nurse Corps. “It was horrible,” she says. “I was used to seeing blood and death, but seeing 18-year old soldiers in such bad shape from war was very difficult.” Witness to the Tet Offensive, she was stationed at a camp that was overrun by the Viet Cong.

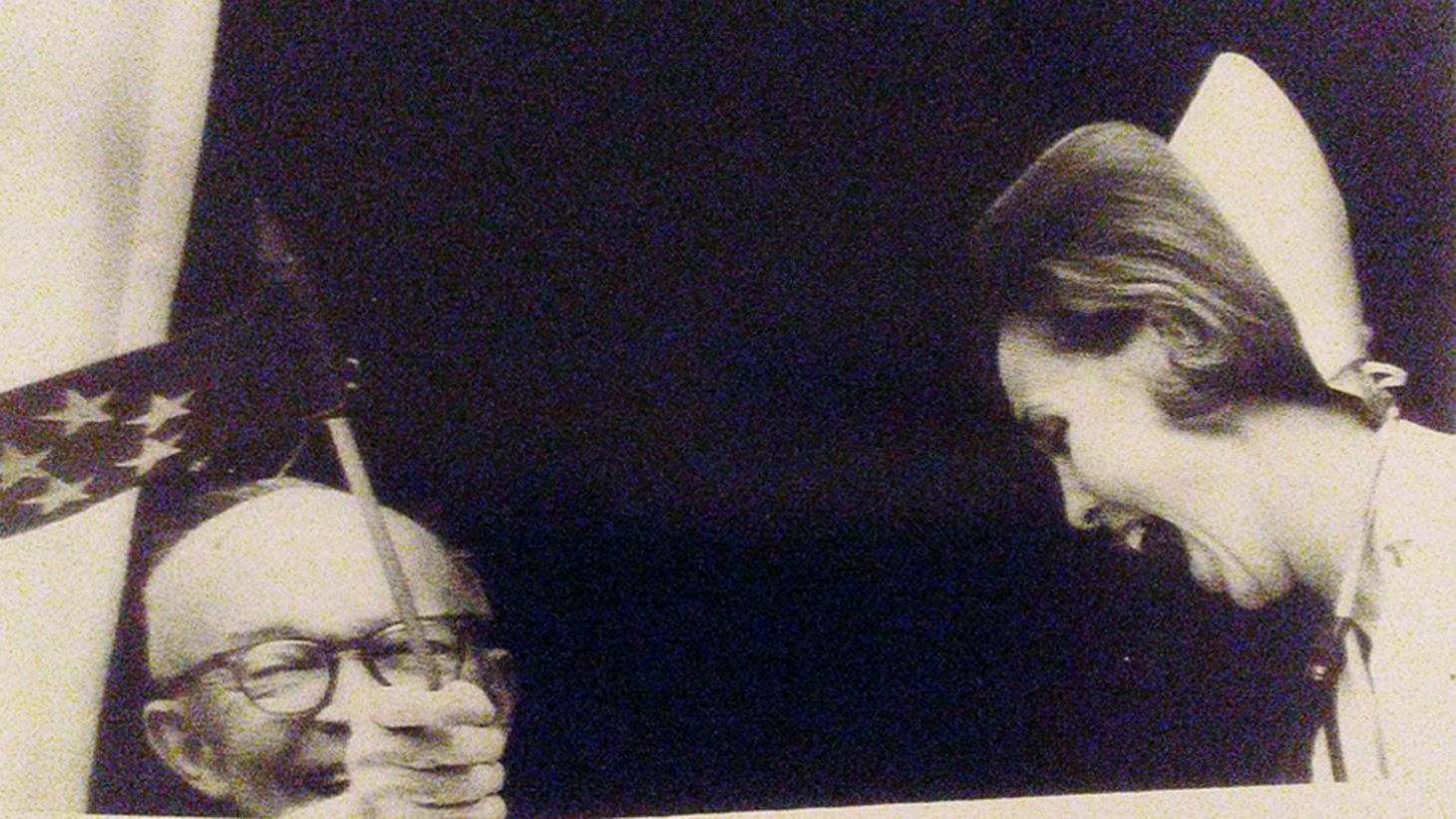

By mid-1968 she was back on U.S. soil. Karen was stationed at Walter Reed Army Medical Center (now called Walter Reed National Military Medical Center) in Washington, D.C. when the Surgeon General of the United States Army, Leonard Heaton, stopped to visit one of her patients. Unaware of the guest’s high rank, (he was dressed in civilian clothes and she didn’t recognize him), she firmly said “no” to a visit — she had just delivered pain medication and the patient needed to rest.

The next morning, Karen was called into an office where she encountered the Surgeon General, this time in full military regalia. Impressed with her actions the day before, he reassigned her to his floor at the medical center. She spent the next 10 and a half months caring for her most famous patient to date, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, five-star general and 34th president of the United States, before his death in 1969.

After her stint at Walter Reed, Karen was assigned to nurse recruiting duty in Chicago until 1972. During those volatile late war years, her military vehicles were firebombed and covered in paint by anti-war protestors. She was even once arrested while walking down the street in uniform, the police mistaking her for a protestor.

A four-year assignment in Hawaii at Tripler Army Medical Center followed. For the first time in her career, she was stationed in an emergency department, a medical specialty that would quickly become Karen’s practice of choice. “It’s an adrenaline rush,” she said recently about the field where she still works more than 40 years later. While there, she completed her master’s degree at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa.

During the late 1970s, Karen took assignments in Kansas, Washington, Washington D.C. and Georgia. “I didn’t even know if I was going to stay in the Army,” she said with a chuckle. “I ended up having a career without even realizing it.” By 1987, she had risen the ranks to Lieutenant Colonel.

She retired from the military only to take on a new career as a financial planner for 12 years, and then return to nursing. She has worked in EDs in Georgia, South Carolina, Florida and, most recently, Louisiana. Karen now shuttles between part-time work in Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans and her home in Pensacola, Florida.

“My husband keeps asking me if I’ll retire,” the nurse of more than 50 years said. “I can still walk, talk, chew gum and run around most of them,” she remarked jokingly about her younger colleagues. “Maybe in two or three years.”